December 21, 2021|Updated December 21, 2021 at 5:05 p.m. EST

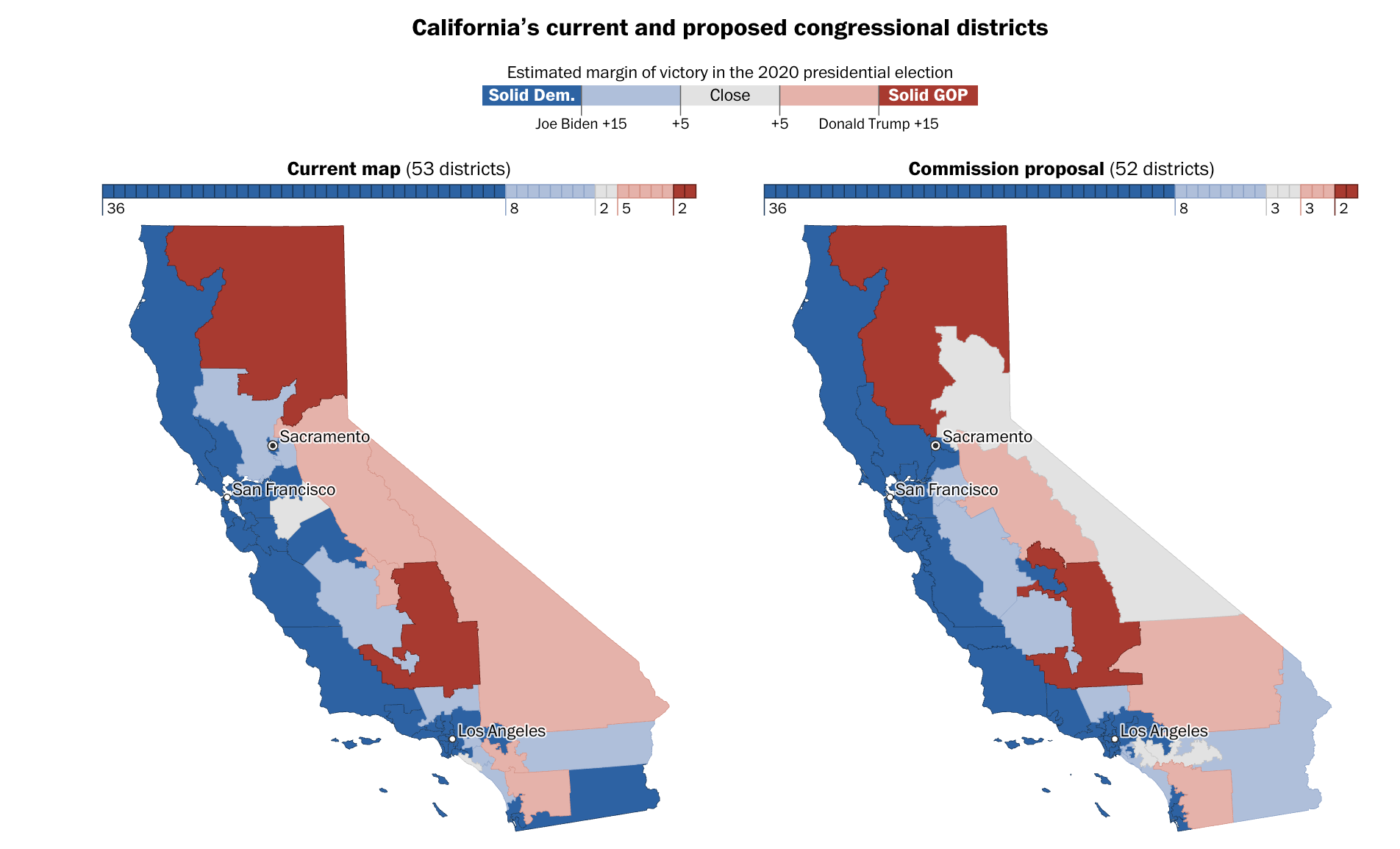

A newly approved congressional map for California increases the number of majority-Latino districts in the state and creates more difficult terrain for Republican candidates.

The new map protects 41 Democratic-held seats with districts President Biden would have won by double digits. Five of the 11 current Republican members are shifted into more Democratic territory, setting up California as a potential battleground ahead of a fierce clash for control of Congress. Democrats hold a razor-thin U.S. House majority, but Republicans have drawn maps in other states that give them an edge in the 2022 elections.

Latino citizens of voting age make up the majority in 16 districts, up from 13 in the current map, according to an analysis by Paul Mitchell, a redistricting expert who runs the California-based Redistricting Partners, which consults on map drawing. Latinos are 38 percent of California’s population. If all of the 16 newly drawn seats were filled by Latinos, they would make up 30 percent of the California House delegation.

An independent citizens redistricting commission that drew California’s map approved its final lines on Monday.

In a strong Democratic year in California, the current House delegation of 42 Democrats and 11 Republicans could lean as much as 47 to 5 under the new plan. It is the second to be created under the commission, which was approved by voters to take redistricting out of the hands of elected politicians. At least four seats are expected to be hard-fought toss-ups. Overall, the state will go from 53 seats to 52.

“On paper, the map here is great for Democrats,” Mitchell said. “It’s definitely ripe for a pickup of two seats, and helps the national map a little bit in balancing out the gains Republicans have had in states they could totally gerrymander.”

[Ohio Republicans’ redistricting map dilutes Black voters’ power in Congress]

An example of the potential benefits to Democrats is the new 22nd Congressional District, located in the state’s expansive Central Valley. It is represented by Rep. David G. Valadao, a Republican who lost his seat in the 2018 Democratic midterm wave and won it back in 2020.

Valadao, who is one of the 10 Republicans who voted to impeach President Donald Trump over his role in the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, will face an even more Democratic electorate next year in a district Biden would have won by 13 percentage points and in which nearly 60 percent of potential voters are Latino. Valadao previously prevailed in a district Biden won by 11 percentage points.

Valadao lost some of his more Republican territory to House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R), whose new 20th District juts into Valadao’s current district like an outstretched arm.

“If Democrats are going to control Congress, it’s my prediction that will happen because a bunch of 18-year-old Latinos showed up to vote in the [Valadao’s] district and flipped that seat,” said Christian Arana, vice president of policy at the Latino Community Foundation.

The nation’s most populous state ceded a seat because of census population statistics, which rewarded faster-growing states such as Texas, Florida and Colorado. But the one demographic that did rise in numbers since the last redistricting a decade ago was Latinos, particularly citizens of voting age.

The California commission’s recognition of Latino growth stands in stark contrast with Texas’s redistricting. More than 50 percent of its population boom came from Latinos, yet the GOP state legislature did not draw any new Latino-majority districts. The Justice Department is suing Texas under the Voting Rights Act, claiming Republicans intentionally minimized Latino voting strength to draw more majority-White districts.

[Texas GOP lawmakers’ redistricting map doesn’t include new Latino-majority seat]

California Latino advocacy groups and Democrats largely saw the new map as a win, given that the state’s Latino voters have overwhelmingly supported Democratic candidates.

“The Republican Party is overwhelmingly White, non-college-educated voters. When you have a legislature drawing maps like in Texas, you can get creative and maximize your position,” said Mike Madrid, a California-based GOP consultant with expertise in Latino voting trends. “The long-term trajectory is competitive seats will go Democratic. The Republican Party’s best hope is to build a wall around as many congressional districts as it can to stave off the inevitable.”

In California, Republicans may hold the competitive seats in 2022, but by the end of the decade, “they will absolutely lose those seats,” Madrid said.

Of California’s 22 million registered voters, only 24 percent were Republican, according to the last state tally in August. Nearly 47 percent were Democrats, and another 23 percent were nonpartisan, a group that has traditionally sided largely with Democrats.

Looking beyond 2022, Mitchell said, Democrats will have opportunities to peel off more seats from Republicans such as Reps. Tom McClintock, who represents the exurbs of the Bay Area to which people fled during the coronavirus pandemic for larger homes and yards; Michelle Steel, whose Orange County district now dips into Los Angeles County; and Ken Calvert, whose district stretching from Los Angeles County to Palm Springs has increasingly robust Latino and LGBTQ communities.

Democrats took one hit in the new map. The loss of one congressional seat came at their expense in Los Angeles County, where population has sagged over the decade. The new map merged two Democratic districts now represented by Reps. Alan Lowenthal and Lucille Roybal-Allard.

Lowenthal announced last week that he would not seek reelection. Hours before the final map was approved Monday, Roybal-Allard also said she would retire. Both are 80 years old. Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia, an ally of Biden and Vice President Harris, is the highest-profile candidate so far for the merged seat.

Asian Americans, another diverse and growing demographic, successfully fought moves they saw as weakening their political influence. An original draft map sliced up Asian-majority cities in the West San Gabriel Valley, represented by Rep. Judy Chu, (D) the first Chinese American woman elected to Congress.

The proposal drew immediate backlash from the local Asian community, and the commission kept the cities together. In all, in a state with a 17 percent Asian population, the map contains six congressional districts where 30 percent or more of the citizens of voting age are Asian.

“In this moment, I feel relief. At least we’re together,” said Nancy Yap, executive director of the Center for Asian Americans United for Self Empowerment (CAUSE). “We wanted to ensure our political voice was preserved. … I appreciate that we’ve been heard.”

The California Citizens Redistricting Commission, approved by voters ahead of 2011 redistricting, is considered a model for the kind of independent panels that civic groups say are needed to end partisan gerrymandering and bring greater transparency to a complicated process. With a state as large and diverse as California, the citizen commissioners had to weigh many competing interests and at times faced intense criticism.

“Democracy is a messy process, and the beauty of commissions is that it’s all done live and open in a transparent way so everyone gets to see the messiness,” said Sara Sadhwani, one of the 14 commissioners. “There are a lot of commentators on the sidelines that like to sneer and jeer at us, but I think we were successful.”

One of the commission’s most vocal critics, Steven Maviglio, a Sacramento-based Democratic consultant, lamented that under the voter-approved system, Democrats gave up too much power. If Democratic politicians drew the lines, “it would be the hardball politics that other states are playing, and the creativity that goes with that is endless,” he said, suggesting they could have drawn themselves more seats.

As Maviglio noted, most Republican-held states are drawing sharply partisan maps, while the largest Democratic state was leaving it to a citizen panel.

“California is a chump for taking this on so early,” he said.

Adrián Blanco contributed to this report.